What the Stone Remembers

I think of how we preserve what we cannot keep—how the stone remembers

what the flesh forgets.

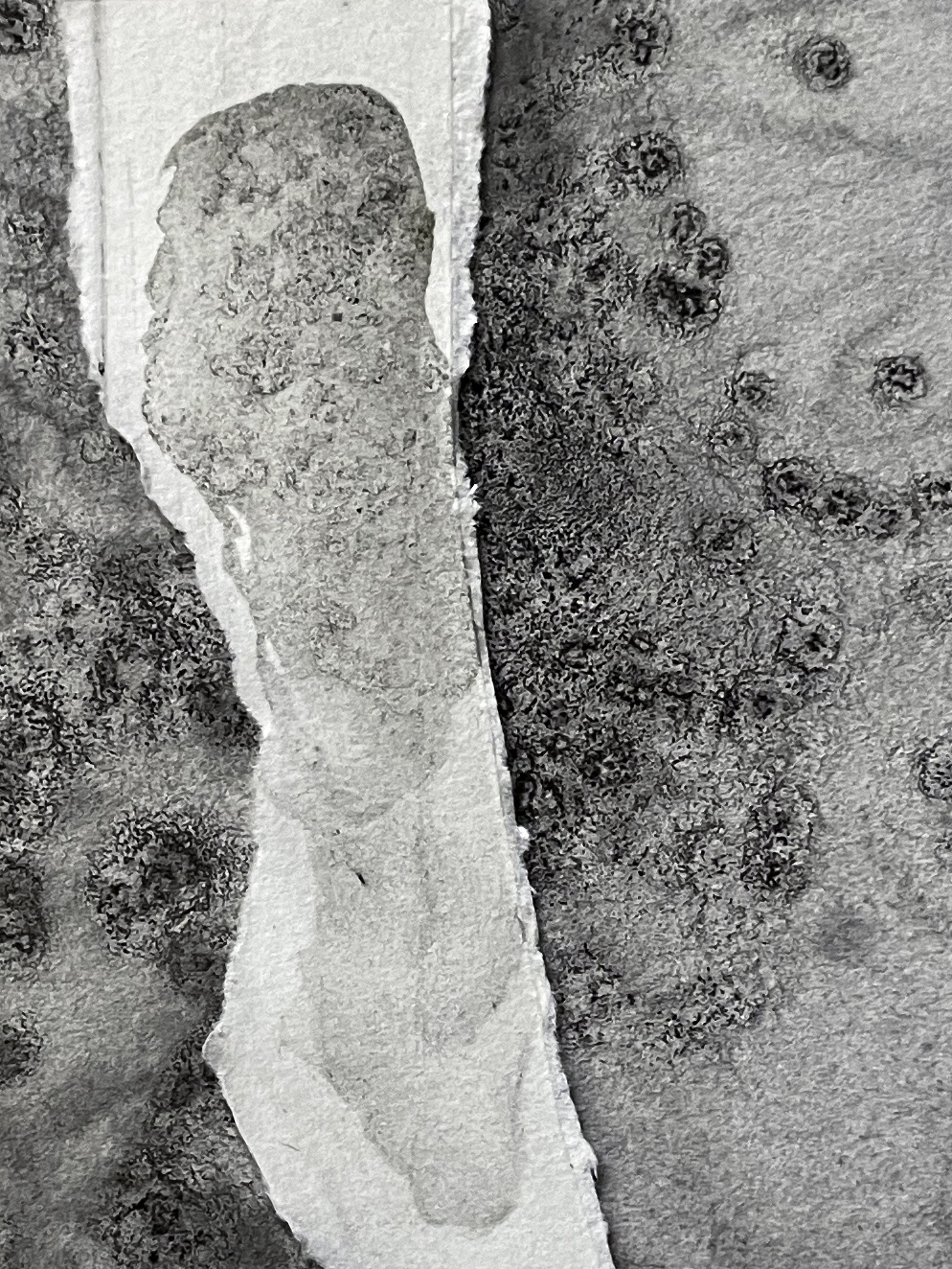

Here, in sediment the color of mourning, a plant once pressed its green mouth to sunlight, before the earth swallowed it whole. I think of how we preserve what we cannot keep—how the stone remembers what the flesh forgets.

In Seoul, there is a woman whose hands once held me, whose milk I drank before language divided us like continents. Her fingerprints, fossilized in my marrow, a archaeology I carry but cannot read.

The paleontologist tells me how pressure creates preservation: weight over time equals permanence. I think of the weight of not knowing, how it presses my mother tongue into silence, leaves only the impression of what was once alive.

Ma, I whisper to the fossil, eomma, I say to the stone. The Korean spills from my mouth like sediment, each syllable a small burial.

As I carefully untangle my past from overtaking my present, I am aware of the delicacy of the fibrous nature in which it shreds, splits, and severs if not tended with the utmost care and respect—

how memory, like this ancient fern, can crumble at the wrong touch. How some preservation requires forgetting. How some forgetting is its own kind of love.

In the photograph, branching veins reach toward what was once sky. I trace them with my finger, these pathways to nowhere, and wonder if somewhere in Seoul, a woman is tracing the same lines in her palm, wondering if they lead to me.

The fossil does not answer. The stone keeps its secrets. But here, pressed between then and now, I am learning that some things survive not by staying whole but by leaving beautiful breaks.

Night Writing on My Mother's Good Ear

Mother's ear pressed to paper—

or is it the moon, listening

through the moth-eaten dark?

Mother's ear pressed to paper—

or is it the moon, listening

through the moth-eaten dark?

In sleep, I am both

the brush and the water,

the leaf turning silver

before it knows it will fall.

You appear

like calligraphy bleeding

through rice paper:

first the shadow,

then the word,

then the ache

of meaning.

Each breath sketches

another wing—

graphite dust

on my tongue,

teaching me

how things dissolve:

First the body.

Then the name.

Then the space

between your hand

and the morning

it reached for.

In this language

of smudges and stains,

even decay

holds light—

each petal

a door

closing

softly

on its own

ghost.

Portrait of Water Teaching My Tongue the Word for Home

the way this red line

pulled taut between

here and there

the red string

makes mapping

possible

Charcoal swirls like smoke

from my grandmother's kitchen—

the way she drew infinity

with her wooden spoon

in broth that held

our hunger.

needle threaded coves of branches

shelter my weaving loom

Here, water learns to speak Korean,

stuttering over stones

the same way I stumble

through 안녕

my tongue still foreign

to my own mouth.

Fallen logs become bridges

become barriers

become the way we cross

what cannot be crossed—

sticky humid moss grows

kin that never leaves home

And on concrete, the red string

manifesting connection for the future

thinner than my mother's patience

stronger than the ocean

that I crossed

leaving her there

in a country that tastes

like home and remembering.

I draw hair gathered

to interlace into nets

The thread knows what I am learning:

that home is not a place

but a current

that flows beneath

everything we touch—

the way water finds water

the way blood calls to blood

the way this red line

pulled taut between

here and there

the red string

makes mapping

possible.

In Korean, we say

빨간 실

red thread—

the invisible cord

connecting us

to what we're meant

to love.

I am still learning

to trust

the pull.

Self-Portrait as Tea Bag Split Open Over My Grandfather's Woodblocks

You said the concrete holds ghosts.

Every slab poured over another slab.

I.

Tea bag split open on the kitchen counter. Brown leaves scattered like ash like the wooden blocks your grandfather hid beneath the house. Each letter carved backwards so the truth could bloom forward.

A bee heavy with yesterday's nectar crawls across hot pavement. Block by block the city cooks itself to fever. Even she knows this is holy ground— where small wings still choose to land.

II.

You said the concrete holds ghosts. Every slab poured over another slab. The original roads buried but still breathing underneath.

Watch: the bee stumbles between sidewalk cracks where jade plant tea someone spilled last summer still stains the stone green as unspoken grief.

III.

In my mouth: bergamot bitter as the news that came in brown paper. In my mouth: words your grandmother carved into kindling when kindling was all she had left to speak with.

The wooden blocks scatter across my table like dice after empire played its hand. Each character gouged deep enough to survive burning. Deep enough to bleed ink onto paper thin as your mother's letters that never came.

IV.

Look at the nest: two white eggs waiting for heat that may never arrive. But she builds anyway— grass and wire and hope, mapping her small country in the space between branches that bend but refuse to break.

Your pencil traces the photograph's borders. Occupation lines drawn over and over until the paper nearly tears. But see: even now the eggs gleam like promises that some songs cannot be colonized.

V.

The tea bag bleeds brown into clear water. The bee lifts from concrete, disappears into the space between what was documented and what actually breathed.

In the pavement: blocks of memory cooling in evening air. In the nest: two white worlds waiting to crack open.

In my hands: these wooden letters that spell your name in a language they tried to bury beneath their roads.

Tomorrow someone will find these blocks, will wonder what stories the wood remembered. Tomorrow the eggs will hatch or they won't.

Either way— this insistence on building home in the unmappable spaces. This stubborn blooming between the cracks.

Brief Cartography

Mother—is that what I call the woman who held me for three days before the world took me away?

Mother—is that what I call the woman who held me for three days before the world took me away?

I am learning to perforate my own face. Each nail hole a day I didn't have with you, each tear in hanji paper

another way to breathe around the absence that shaped my lungs.

In the microscope of memory, your fingerprint becomes a country I visited once, briefly, like a tourist in my own skin.

Salt-soap rivers carve through marbled ink—this is how we make ourselves visible: by erasing what we never had.

I imagine you walking me to school, but instead I wrap paper around my own head, golden like the makeup

that makes me almost white, almost someone else's daughter. The gravel catches light the way your voice might have

if I had learned to listen in a language you gave me before they gave me English words for abandonment.

I draw my face looking at someone else's reflection— yours, perhaps, in a mirror I never learned to hold.

An orphan with your name but lighter dreams, whiter skin that never touched yours long enough to know

the true shape underneath. Brown as earth, stubborn as the stones that remember three days of your heartbeat

against mine. Tell me, what is the word for loving someone you barely knew but who lives in every breath?

What is the word for home when you are the distance between a mother's arms and the empty space

they left behind?

The Distance Between Shutter and Release

Three polaroids scattered

like prayer cards on cotton—

each frame a door

I cannot walk through

but must.

Three polaroids scattered

like prayer cards on cotton—

each frame a door

I cannot walk through

but must.

The water knows

what the camera

cannot hold: how light

becomes longing,

how distance

dissolves in silver halide.

I press my palm

to the photograph's surface,

still warm from development,

and suddenly—

I am kneeling

at the river's mouth,

moss soft beneath

my borrowed knees.

In the blurred edges

of what was captured,

I find what was lost:

the exact temperature

of afternoon air,

the way water

speaks in tongues

I almost understand.

Tonight, these images

arrange themselves

like stepping stones

across my bedsheets—

each one a small bridge

between who I was

at the water's edge

and who I am

learning to become

in this fluorescent room

where rivers exist

only in the space

between shutter

and release.

Water Refusing Its Own Tea

In the morning, I unfold yesterday's tea—cold now, a persimmon bruise spreading through hanji's breath.

In the morning, I unfold yesterday's tea—cold now, a persimmon bruise spreading through hanji's breath. Three days. That's all the mother my hands remember. Each fiber refuses me. I press graphite into what won't be pressed, dust settling like the ghost of her palm I never learned. This is how I practice porousness: watching color roll from the paper's edge like a body I was pulled from too soon. I crumple with the tenderness reserved for photographs never taken. In Korea, they have a word for the space between: jeong, which grows even in absence, especially in absence. My fingers search the hanji for her fingerprints, for the maker's mark that says you are from here, from this. But the paper holds only my own failed attempts at steeping— as if I could brew a mother from memory, from three days stretched across a lifetime of mornings like this one. I fold myself smaller, hoping to fit inside the space she left, to be both the question and its echo. Mother taught me nothing. So I teach myself: to fold paper is to fold time backward, to the moment before leaving became the only thing we shared.

Self-Portrait as Return Address

Do you know the sound a snail makes when it thinks no one is listening?

Do you know the sound a snail makes when it thinks no one is listening?

I draw it anyway. Small. Spiral. The way you taught me to hold a secret— cupped like water between two palms.

In Korean, to return is dol-a-ga-da but I can't roll the syllables without tasting your name.

Look— even this creature carries its house on its back. Even this blue wash of paint knows how to bleed beyond its borders.

They say if you're fixated on one thing you miss what's next but I keep drawing the same shell the same curve of spine disappearing.

Do you see how I've made a home of this waiting?

American Tongue

Do you know I draw spirals when I'm thinking of you?

Mother, I call you this though I never learned the Korean word for hunger.

The persimmon sits on my counter, orange as the sunrise you might have seen the morning you let me go.

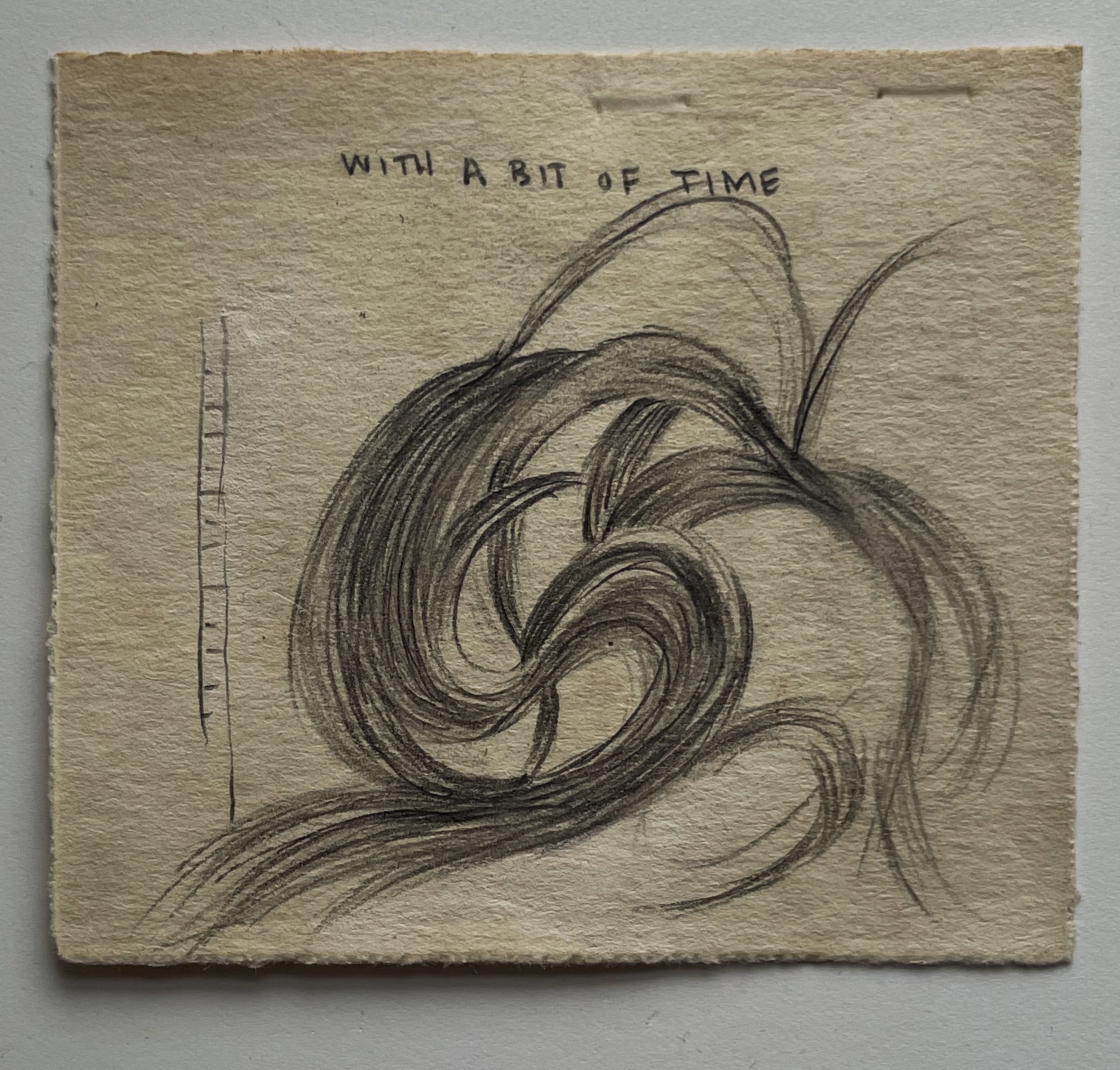

With a bit of time— the goldenrod dies into something beautiful. Its seeds scatter like the questions I swallow each morning with my coffee.

Do you know I draw spirals when I'm thinking of you?

My hand moves in circles, consciousness enacting what blood remembers: the shape of your womb, the curve of your grief.

Today I ate a persimmon and tasted a country I've never seen. Sweet flesh dissolving on my American tongue.

With a bit of time, even orphans learn to mother themselves.

The flowers know this— how dying is just another word for becoming.